Translation Styles Contents

Welcome to the fourth article in our eight-part series on how to get the most out of your translation. This series of articles is intended for readers who need to get their message across clearly, in a foreign language. Specifically, it deals with issues related to Japanese to English and English to Japanese translation.

This table of contents will be updated with links as I publish each new article.

- How Important is Translation Quality, Anyway?

- Translation Sin 1: Automated Translation

- Translation Sin 2: Non-native Translation

- Translation Sin 3: Direct Translation

- Translation Necessity 1: Consultation

- Translation Necessity 2: Communication

- Translation Necessity 3: Trust

- The Final Product

Recap: The Wrong Tools

Our last couple of articles talked about using the wrong tools for translation: Software and non-native linguists. I hope I have successfully conveyed how neither of these sources are appropriate for a professional translation. In the latter case, even the team of a non-native translator and native editor is going to result in an inferior product when compared to the quality you get from having a dedicated, native translator.

That said, even if you hire a professional translator, you can still wind up with a lousy product if you commit:

Translation Sin 3: Direct Translation

First, a quick definition: When I say “direct translation,” I’m talking about sentence-by-sentence translation. As such, this definition of “direct translation” allows for changing word order as necessary, as well as adding or removing the subject and/ or object of the sentence, as necessary (either or both are frequently missing in Japanese). I will talk about formalities, below, as an extreme example of direct translation gone wrong, but for most examples, I will leave them out.

Direct translation does not allow for: removing content sentences, adding content sentences, breaking up sentences, or rearranging sentences within paragraphs. The same restrictions apply to larger blocks of text as well. I have seen direct translation taken to the point where individual words could not be added or deleted, but criticizing that sort of extremity would be like shooting fish in a barrel, and I had my fill of barrel shooting in the previous two articles.

If using a non-native translator is like bringing a knife to a gun fight (and using automated translation is like showing up unarmed and blindfolded), then shackling your professional translator by insisting on direct translation is like buying the finest firearm on the market. . . and no ammunition. All the shortcomings covered in the article about non-native translators apply in equal- or greater- force to direct translation. Whereas it is merely a strong possibility that a non-native translator will fail to connect with your target readers, with direct translation, it’s a guarantee. With translation, you have a choice:

Translate Words or Translate Meaning

You can’t have it both ways, especially when you’re dealing with languages as grammatically and philosophically different as English and Japanese. If you want your message to resonate with an audience from an entirely different cultural base- or even sound fluent- ideally, you want to give your translator the freedom to rewrite your words in order to preserve the ideas. I’ll talk about trust in detail in a later article, but for now, suffice it to say that without trust in your professional translator, it’s easy to fall into the trap of demanding direct translation and thereby sabotaging your own product.

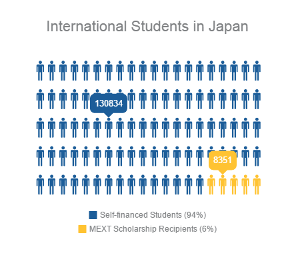

At the most basic level, writing style has to change. In order to avoid direct address, which is considered to be rude, Japanese is often written in passive voice. In English, passive voice is considered to be poor grammar (I had a professor that docked 10% from a paper’s grade for each use) and avoiding direct address makes the writer sound weak. Japanese writing is peppered with adverbs, whereas English shuns them. The Japanese, in my observation, have a superhuman tolerance for bureaucracy and paperwork. Americans are going to want to know why they have to fill out those 17 different forms. Wordiness is a way of life in Japanese, but it gets worse when rendered into English. Here’s an example that affects international students:

- Japanese: 資格外活動許可

- Japanese romaji: shikakugai katsudo kyoka

- Official English translation: Permit to engage in activities other than that permitted under the status of residence previously granted

- Meaning: Work Permit

Not only is the official translation absurdly long and wordy, it’s so indirect that it fails to convey any appreciable meaning. This is an example of a translation that gave no consideration to the target audience, as I will discuss below. It is written in such a way that it perfectly explains the process to the agency that created it, but makes no sense to the applicant for whom it is designed.

Address Your (New) Audience

In the first article in this series, I equated translation to advertising because the purpose in translating material for public consumption is to gain the attention of an additional demographic. It should go without saying, but a customer with a different linguistic background is probably going to have a different cultural background, as well. It is not enough to simply change the language from English to Japanese, you need to consider the cultural differences between your readers in each country. This means, to a certain degree, you’re going to need to let your native translator transform the wording in order to maintain your meaning and impact.

Obviously, if you directly address your audience in the source language, that language is going to have to change. I have on my desk a graduate school flier, for a graduate school of international relations, no less, that states the school’s goal in English: “Cultivating professionals capable of leading Japanese Internationalization and being active internationally.” Ignoring the inexcusable repetition for now, this is clearly a direct translation of a message intended for a Japanese audience. I’m not sure how this is supposed to appeal to anyone who isn’t Japanese (Japan’s formal institutions will roll over and die before permitting a foreigner to lead “Japanese Internationalization.”) Either the translation company failed to interact meaningfully with the graduate school (we’ll cover communication later), or the school insisted on direct translation. In any case, someone failed.

Even in less egregious examples, it is important to realize what your target audience cares about. I have several graduate school fliers (yes, I collect them), that begin with the school’s year of establishment and the history of its growth and addition of fields of study over the past century. I can’t say for sure whether this is as snooze-worthy to a Japanese audience as it is to me, but it’s not nearly dynamic enough to attract an American audience. These schools would have been better served by allowing the translator to throw out the entire paragraph- or at least bury if deep enough in the pamphlet that it could only be found by someone who was already “hooked.” Your translator should also be your cultural liaison, so you help yourself by allowing that person the freedom to make necessary content and organization changes.

Extreme Examples

In some cases, I have seen more extreme examples of direct translation but these, in almost every case, were the products of non-native translators. Some Japanese to English examples that I see regularly are: “Let’s enjoy together” (楽しみましょう!) and “Please be nice to me.” (よろしくお願いします). Other common examples are the inclusion or omission of customary formalities and greetings. Since these appear most often in non-native translators’ works, they generally reflect a lack of understanding of the target culture’s norms. I have, however, seen them in native translators’ work, when those translators were pressured into direct translation.

Why Direct Translation Happens

I can only think of two explanations for direct translation: ignorance and fear. Ignorance, in this case, applies to organizations that don’t realize that their translations need to sell. Either they do not understand that translation = advertising, or they do not realize that they need to change their words to retain their meaning.

Fear applies when the organization’s leadership cannot understand the translated material and is unwilling to allow the translator to stray from their “approved wording” in the source language. To an experienced observer, a direct translation reveals the underlying ignorance/ fear and exposes the organization’s poor preparation for internationalization.

Getting Your Meaning Across is Not Enough

Really, this is the point of this entire series of articles. When you engage a translator for your business, remember that you don’t need to get the gist of your message across, you need to deliver a knockout punch! Just like advertising, you need to grab your readers’ attention and hold it. A direct translation, with its stilted sentences and confusing organization, is never going to cut it.

On to the good stuff

Our next three articles talk about the necessities of translation, so I can finally stop scowling as I write. The first topic will be Consultation, the first step towards your effective translation!

To keep up to date on all of TranSenz’s new articles and news, visit our Facebook page and “Like” us to get our news stories in your feed!

Hi! I just stumbled across these articles through Google. As a Japanese to English translator myself, I have to say they’re a great read.

Anyway, in case it hasn’t already been pointed out already, I just wanted to say that under “Why Direct Translation Happens”, you mention three explanations but you only list two. Hope you don’t mind my pedantry – it just stood out as I read through.

Thanks for writing these great articles and best regards,

Nick

Hi Nick,

Thanks for the catch! I never mind pedantry.

I think I must have had a third reason in mind when I wrote the article, but I can’t figure out what it was supposed to be anymore.

I’ve gotten out of translation, so, without any sense of competition, I wish you the best of luck in your business!

Good Luck,

– Travis from TranSenz